Why Is Managing Florida Springs So Complicated?

by Derek Reiners, Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Florida Gulf Coast University

|

Institutional Complexity

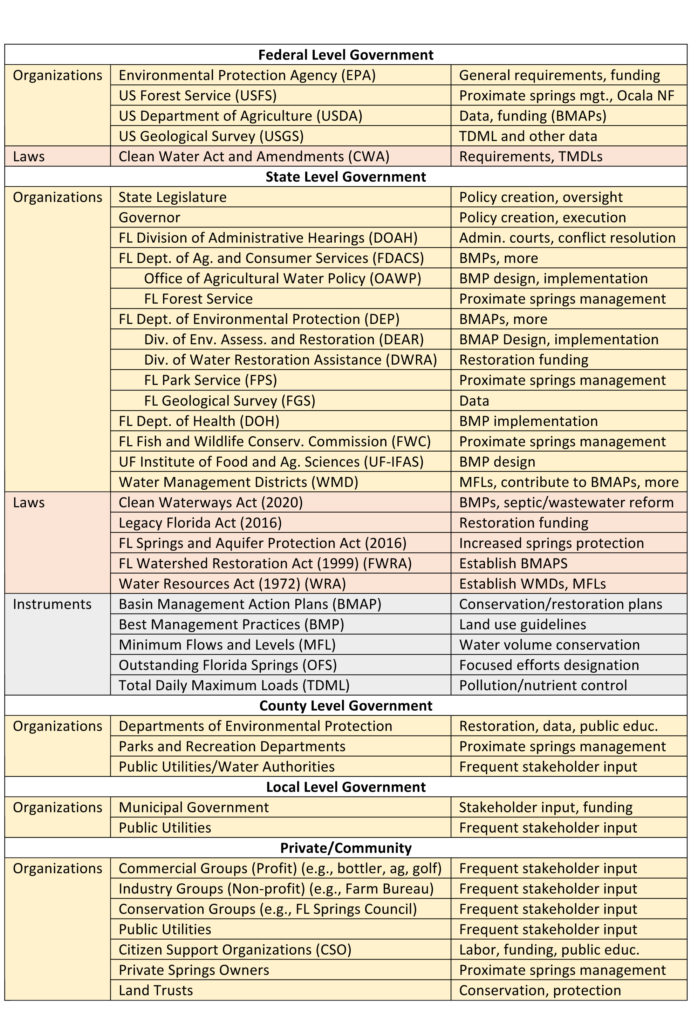

Caring for Florida springs involves a complex network of politicians, departments, and agencies providing laws, funding, data, and policies at every level of government (see Table 1 at the bottom of this page).

The policy and politics of Florida springs can be complicated but it can be greatly influenced by citizens.

At the federal level, just a partial list includes the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), U.S. Forest Service (USFS), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and Congress’s Clean Water Act.

Florida county and city governments, some of which directly own and manage springs, contribute to springs management via parks and recreation departments, environmental protection departments, public utilities, and other entities.

Still, most of the action is at the state level, where five water management districts (WMDs), the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC), the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF-IFAS), and agencies of the departments of Environmental Protection (FDEP), Health (FDOH), Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS), among others, all contribute variously to the design and implementation of springs management instruments such as Basin Management Action Plans (BMAPs), Total Daily Maximum Loads (TMDLs), Minimum Flows and Levels (MFLs), and Best Management Practices (BMPs), stipulated by laws such as the Water Resources Act (RWA 1972), the Florida Watershed Restoration Act (FWRA 1999), and the Florida Springs and Aquifer Protection act (2016).

It’s an alphabet soup. And it should be noted that most of these institutions focus on broad ranges of issues, many of which do not directly relate to water. Even the institutions that focus specifically on water may only affect springs insofar as springs are connected to aquifers and surface waters. Springs management is largely lumped in with other, broader water management concerns such as overall quality and supply. Moreover, until about the last five to 10 years, it could be argued that the springs were a bit of an afterthought.

Drawbacks of Complicated Management

Management processes and outcomes under such complex, conglomerated institutional arrangements can be viewed as fragmented and inconsistent. For example, currently, the primary framework for the protection and restoration of springs, BMAPs, does not involve MFLs, which many argue is a fundamental management consideration of spring “health.” But establishing MFLs is a separate process undertaken by separate entities under separate management considerations.

In a general context, coordination between the various individuals, departments, and agencies involved can entail high transaction costs – that is, extra time, information, and effort required to achieve a goal, such as restoring the ecological balance (or at least historical balance) of plants and algae in a spring run. High transaction costs also tend to translate into high economic costs, opportunity costs, and generally make goals and mutually beneficial outcomes less likely to be achieved (North, 1990; Williamson, 1999).

Highly complex and technical policy arenas can also amplify the influence of special interests. It doesn’t have to be a conspiracy or necessarily purposefully set up to favor certain interests. It’s usually because, even in highly democratic and transparent processes, the individuals and groups that dedicate the large amount of time and resources necessary to learn about and influence these kinds of policies are individuals and groups that are likely to benefit from or be harmed by them in a measurable, often financial manner (Wilson, 1980).

People who attend BMAP and other springs management meetings know that public participation usually does not reflect the public in any demographic sense. Rather it’s an orbit of interests and “technocrats” from agencies, utilities, engineering firms, agriculture, universities, and environmental groups. This is not to say that these persons all have the same perspective. But lessons from policy arenas such as regulating nuclear power plants (see Temples, 1982), for example, have shown that technical complexity can help create a kind of bulwark against diversity of input, particularly on behalf of the public interest.

Why Not Simplify and Focus Springs Management?

Springs like the Ichetucknee are not simply aesthetically different configurations of fresh water that can be easily substitutable with lakes and rivers. Springs result in the creation of legitimately unique ecological, recreational, and cultural oases that provide biological and experiential phenomena found nowhere else. So, from a management perspective, why not treat springs as the coherent set of entities or systems that they are – that is, as the basic unit or target of holistic, focused management, perhaps even under a specialized agency where the concerns of managing recreation, keeping the runs clean, managing vegetation and wildlife, regulating volume and flow, reducing nutrients and pollution, and other concerns are all considered together? Would that not be better than hoping that dozens of disparate institutions felicitously work in harmony for the benefit of springs?

One of the simplest reasons that such a reform might be difficult is that many springs (including the Ichetucknee River) rise and flow through multiple management and property rights jurisdictions, which can include private, city, and county lands, as well as different agencies and departments at the state and federal levels. But (pun halfheartedly intended) it’s much deeper than that. Springs are considered to be groundwater in addition to surface water. Therefore, protection of the very attributes that are unique and valuable about spring water (e.g., clean, clear, beautiful, abundant) must necessarily include groundwater management and everything that comes with it. This is extensive, involving water withdrawal permitting, wastewater and stormwater management, policing dumping, etc. And since fresh groundwater can only be recharged by rainwater seeping through land, groundwater management merges heavily with land use management, including many regulations associated with zoning, urban development, agriculture, utilities, and more.

So, combined with surface water considerations, flora and fauna management, and more, it would be difficult to manage springs in any comprehensive manner without the involvement of different entities, laws, and strategies. Further, for a truly comprehensive approach, one could even argue that, due to the effects on springs of changes in rainfall, storms, and sea levels associated with climate change, a springs management regime might involve these associated institutions as well. In practical terms this might not include broader mitigation efforts, but it might include springs-focused adaptations.

Another reason for the complexity in springs management is historical institutionalism, which explains present-day institutions based on their connection to and evolution from the prior institutional foundations upon which they are built. Once an institutional foundation is laid, despite changing circumstances and needs over time, that foundation may change very little (Pierson & Skocpol, 2002). Instead, new circumstances and needs are often met in an additive, incremental fashion, where new responsibilities, budgets, and offices sprout and grow from the original foundations (Lindblom, 1959). The key point is that institutions that evolve in such a way may not be as efficient as they would be if they were able to be fundamentally redesigned in the face of new priorities. This same dynamic, known in broader terms as path dependency, appears in other contexts as well, such as biological evolution (e.g., the eye of land vertebrates, which originally evolved in water) and economics (e.g., the persistence of the inefficient QWERTY keyboard).

The bulk of the institutions that we now depend on to manage Florida’s springs evolved from institutions that were developed before springs restoration became a central focus of concern within the larger world of water management (some argue they still aren’t). This does not mean that important institutions, like WMDs, weren’t guided by environmental concerns early on, which they were (see Swihart, 2011). But they, along with most of the many other important players, have to balance many different responsibilities, including accommodating human population expansion.

The Public Can Steer Public Policy

Despite their complexity, springs management policy and outcomes can be affected by the public. In fact, this complexity actually creates a large variety of venues that the public can use to affect policy. Multiple officials, agencies, and processes at multiple levels result in multiple notices, meetings, hearings, elections, and other opportunities for input.

Additionally, policymaking involves different stages (e.g., problem identification, policy design, implementation, etc.). All of these different folds in the policy process create decision-making points along with opportunities to affect them. Shrewd activists understand this and may use a strategy known as “venue shopping,” whereby they purposefully focus their efforts on the venues (perhaps certain courts, processes, or agencies) that are likely to provide the most favorable outcomes to their cause (Schattschneider, 1960). These strategies are available to anyone, but as previously mentioned, the parties most likely to devote significant time and resources to such efforts are the parties who stand to receive concentrated gains or losses.

Don’t have the time and resources to be a full-time activist but still care about the issues? Not to worry; most people don’t either – even many of those who might be affected profoundly (e.g., individual farmers, land owners, etc.). This is why representative organizations exist, usually in the form of non-profits. In the same way that small investors can increase their benefit by pooling economic capital into mutual funds, busy citizens can magnify their impact by pooling political capital (e.g., membership, donations, volunteerism) into “interest groups.” Due to their inherent interests and organization, some groups (such as industry and trade) seem to organize an automatic and almost frictionless fashion. But recent decades have seen a rise in the proliferation and impact of citizen (public interest) groups, which often find success through membership, media campaigns, appeals processes, and education of the public and officials. Different groups focus on different strategies, but the bottom line is that they provide another important type of representation in policy and politics.

Official, institutionalized representation (i.e., whom we elect) is, of course, critical. And, to make wise electoral choices in the context of springs and water management, it is important to have a sense of the various candidates’ general philosophy towards these issues. Elected officials not only determine the content of various laws, but how they will be interpreted and implemented. They put people into decision-making positions with certain values, attitudes, and approaches towards water management. Even if officials are working under the same basic statutory frameworks with the same basic tools, such as The Clean Water Act, Florida Aquifer Protection Act, BMAPs, etc., different officials can emphasize or deemphasize different aspects and/or processes, which can significantly affect outcomes. Further, a governor may choose to fund a statutory program less, more, or the same as previous governors. A governing board of a WMD may choose to emphasize water supply over water quality or vice versa. County commissioners may choose to participate in a cost-sharing program or not. Hundreds of little decisions can add up to big effects on outcomes. Thus politics (i.e., who is elected and what stand they take) can be just as important as policy and the actual laws and regulations that are passed.

In sum, springs management certainly is complex, but that complexity should not discourage citizens from getting involved, because there are very many opportunities and reasons to influence its process and outcomes.

References

Lindblom, C. (1959). The science of “muddling through.” Public Administration Review, 19(2), 79-88.

North, D. C. (1990), Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

Pierson, P., & Skocpol, T. (2002). Historical institutionalism in contemporary political science.

In Katznelson, I. & Milner, H. V. (Eds.), Political Science: The State of the discipline (pp. 445–88). Norton.

Schattschneider, E. E. (1960). The semi-sovereign people. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Swihart, T. (2011). Florida’s water: A fragile resources in a vulnerable state. Resources for the Future.

Temples, J. R. (1982). The nuclear regulatory commission and the politics of regulatory reforms: Since Three Mile Island. Public Administration Review, 42(4), 355-362.

Williamson, O. E. (1999). Public and private bureaucracies: a transaction cost economics perspective. Journal of Law, Economics and Organizations, 15(1), 306-342.

Wilson, J. Q. (1980). The politics of regulation. Basic Books.es