Helping Our Springs

Transforming North Florida From an Extractive to a Creative Economy

by Joon Thomas

The Extractive Economy: Here today, gone tomorrow

Extract: remove, take, take out or obtain, especially by effort or force.

Turpentine, phosphate, fish, timber, water . . . these are natural resources of North Florida, and they have all either been decimated or are declining in quality and abundance. These decimations and declines are the results of an extractive economy, and those results have not been beneficial for the people of North Florida.

The residents of over 80 percent of all counties in the United States earn more money per year than in the 10 counties that hug the banks of the Suwannee, Santa Fe and Ichetucknee rivers. That figure rises to 85 percent of all counties if Alachua County, home to the University of Florida, is omitted from the list. (1) The effects of this impoverishment are even more pronounced than these figures would suggest because the earnings from the extraction of resources were not invested into institutions that would continue to benefit the region into the future. The area surrounding the Ichetucknee has no well-funded foundations, no sovereign wealth fund, no legacy institutions educating our children to go out into the world and prosper; instead, we have a cluster of impoverished rural counties.

Such is the consequence of over a century and a half of extracting resources from North Florida without any reinvestment. This situation is akin to living off the principal of a trust fund; eventually, the original vast sum is depleted. An even better analogy may be the goose that laid the golden egg. In the fable, the goose could only lay one egg per day. Impatient to get the eggs faster, the owner cut the goose open. Such was the end of the harvest of golden eggs.

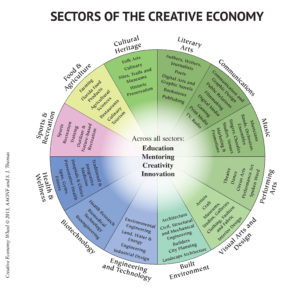

THE CREATIVE ECONOMY CONFLUENCE

is made up of the regenerative capacity of the natural environment; the needs of those who live in that environment, including human beings; and the ingenuity and creativity of people engaged in all manner of activities.

The Creative Economy

There is an alternative to extracting our way into impoverishment. The creative economy depends upon the innovative abilities of human beings rather than on the base value of raw commodities. A flourishing creative economy is embedded in a particular place and is integrated with the creative, regenerative forces of nature itself.

The largest potential sources of wealth in North Florida continue to be land, water, and the creative abilities of the people who live here. Since the 1940s and 1950s, and continuing to the present time, those who make the most money from Florida’s land are those who convert it for the first time from natural wilderness or farmland into residential or commercial use. Thereafter, the increase in value is incremental as the buildings are sold or leased. The big new money is always in paving over more of what is an increasingly dwindling resource. This type of development is clearly visible to anyone who has lived in Florida for any length of time. Coastlines, forests, prairies and wetlands are being consumed by subdivisions, strip malls, office buildings and highways at a steady rate. While it is certainly possible for such developments to fuel a robust economy, that is not the primary reason that such development is being carried out. Rather, it is that the principle of first-time use continues to motivate the conversion of Florida’s land into buildings.

The effect on Florida’s water resources is less visible. The counties of North Florida are blessed with the Floridan Aquifer and other smaller aquifers, a vast underground reserve of freshwater. But in our greed to extract that water faster than it can be replenished, we are cutting open the fabled goose in slow motion. The aquifers have been on a steady path of depletion since the 1930s. It is the aquifers that provide for agriculture, drinking water, household use, and industrial consumption, including cooling for electrical power generation, and it is the aquifers that sustain our world-famous springs and Florida’s rivers and wetlands. As unimaginable as it might seem, we are consuming water at a faster rate than Florida’s heavy rainfall can replenish. Without sufficient water, Florida’s ecology plunges into dysfunction, failing to support both the natural environment and human needs.

It is essential to recognize that a flourishing creative economy goes deeper than what are sometimes listed as the “creative industries.” In the early 2000s, the term “creative economy” became popular to describe what was being recognized as an important economic sector. John Howkins, Richard Florida and other economists realized that ideas and concepts create jobs and add economic value to activities in a way that is different from the traditional breakdown of the economy into extraction, manufacturing, service, and education. (2)

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) described the creative economy as “those activities which have their origin in individual creativity, skill and talent, and which have a potential for wealth and job creation through the generation and exploitation of intellectual property.” (3) UNESCO’s own portrayal of the concept has expanded, and 2021 was named the International Year of Creative Economy for Sustainable Development.

We can learn something by paying attention to the critiques of the early definitions of the creative economy. These descriptions led people to imagine that there was a special class of talented, creative people; that these people were largely urban centered; and that cities were in a global competition to attract this creative class. The list of economic activities deemed part of the creative economy grew so long as to seem to include everything. Why were only some people acknowledged to be creative? Why did they flock to places that served caffé lattes, and what happens when those same caffé lattes are now served in every nook and cranny of America? What were small towns and rural areas supposed to be aspiring to? And how are we to distinguish the creative economy from everything else?

What Takes, What Makes?

We might better divide the economy into what takes wealth, what makes wealth and what manipulates wealth. By this division, the extractive economy takes wealth, the creative economy makes wealth and the derivative economy manipulates wealth. Rather than viewing the economy solely through the lens of primary (extraction of raw materials), secondary (manufacturing) and tertiary (service industries), we can evaluate each activity on the basis of whether it leaves a region with more or less long-term ability to function in an economically viable fashion. To evaluate an economy in this way, we must add in what economists have long neglected to recognize as key economic factors: the long-term health and viability of both the natural environment and the humans who inhabit it.

I began this piece with examples of the extractive economy in North Florida. The turpentine industry was brutal for all who worked in it, damaged the environment, and left behind nothing of lasting value for the environment or human communities. The same can be said of phosphate mining. The waters off the coast of Florida were continually overfished until a net ban was instituted. Nobody would disagree that Florida’s fisheries are no longer as productive as they once were. The original old growth loblolly and longleaf pines of Florida were almost wiped out and replaced with slash pine, a tree of much less economic value. Water continues to be simply given away.

Water: Simply Giving It Away

Water bottling companies generally access the Floridan Aquifer via contract with a private company that owns the land on which the pumping operation takes place. Those private companies pay a one-time permit fee of about $115-$130 to pump water out of Florida’s natural springs (4); that is the only money the State of Florida brings in for allowing private companies to profit from a resource that is held in the public domain.

Joseph Little, professor emeritus at the University of Florida, wants residents to wonder: “Holy mackerel, who owns this water? It’s not owned by the person who happens to own a piece of land. The water doesn’t just fall on this piece of land. The water is flowing underground.” (5)

Water bottling companies pay the same amount—or even less—for pristine Florida water, straight out of the aquifer, than they would pay if they had gotten water from a municipal supply. (6) In return, producers of bottled water in the United States had sales of approximately $22 billion in U.S. dollars in 2018, a number which increases every year (7), and a profit margin ranging from 50 percent to 200 percent. (8)

The water-bottling business takes what is a nationally and globally limited resource and ignores the absolute basics of supply and demand pricing. Not only is it extractive, but also it flies in the face of the capitalist model that the United States purports to place at the center of economic behavior. It would be akin to giving away petroleum reserves. A nation such as Saudi Arabia at least recognizes the economic dead end of extracting a resource that will not be replenished and is attempting to channel a portion of its income into a sovereign wealth fund with investments around the world. North Florida gives away its water at minimal expense, and not a drop of the money that is received goes into any fund for the future.

It is clear that if the core economy of a region is the extraction of basic resources at the lowest price point, the only result can be impoverishment—impoverishment of the environment, of the people, of societal institutions. If a premium is charged for these extracted resources, there is a possibility that people can realize more income in the present and that investments can be made for the future. The experience of petroleum producing nations illustrates both successes and failures in this regard, but if a resource is extracted at a rate faster than it can be replenished, it will be exhausted, usually sooner than later.

The derivative economy is not extractive in the same way, but produces nothing new of value. Rather, it takes the money already in the system and seeks to manipulate it for profit. There must be some source of funds with which to play games, and these are usually the assets of the extremely wealthy. Some locales in the world profit from being centers for stock trades, hedge funds, private banking, tax havens and the legal homes of shell companies; it seems unlikely that this is North Florida’s economic future.

A Creative Vision for North Florida

At its core, the creative economy is centered around a basic and universal human talent, the ability to come up with innovations and improvements and even entirely new ideas. These creations can be “intangible” such as music, art, design, literature, movies, etc., all of which fuel a multi-trillion dollar global industry. But the creative economy is not limited to certain special individuals, types of companies, urban environments or intellectual property. In all locales, but especially in rural areas such as North Florida, the creative economy must be considered as the confluence of the regenerative capacity of the natural environment; the needs of those who live in that environment, including human beings; and the ingenuity and creativity of people engaged in all manner of activities.

A creative economy approach to North Florida would provide a basis for making sound economic decisions. Implementation of this approach can start with some key questions and assessments:

• What are North Florida’s key resource assets?

• What decision-making systems are needed to safeguard North Florida’s natural resources and allocate their use?

• What are some creative solutions to utilizing those assets in a manner that brings in long-term value-added revenue?

• How can we raise our children so that they have a deep understanding of the North Florida environment and so that they develop the creative abilities to live in it wisely?

These are vital questions that can start us on the path from the extractive economy that has dominated and impoverished North Florida towards a creative economy that will restore and safeguard our natural resources and improve the health and financial well-being of our people. In this vision:

• Our farms produce valuable agricultural products that bring in higher revenues while using less water and integrating with our natural environment.

• Secondary businesses utilize this output to manufacture value-added products.

• These secondary businesses support a third tier of businesses that manage and market such products.

• Revenues support a quality education system that prepares future generations to expand on the region’s ingenuity in such areas as water-management, agricultural innovation, bio-medical research (already one of the region’s specialties, this might be expanded to include pharmacological solutions based on Florida plants).

All this is in addition to encouraging creativity in such areas as music, visual arts, culinary production, and so on.

In this vision, North Florida retains its natural resources and utilizes them in harmony with the environment’s own regenerative capabilities while supporting the long-term health and economic vitality of rural, small town and urban communities.

Citations

(1) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_United_States_counties_by_per_capita_income

(2) (https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/12436/concepts/sectors-economy/

(3) https://cvsuite.org/resources/creative-economy/#1494344134942-530f209c-8bbe

(4) https://news.wfsu.org/state-news/2020-02-06/nestles-push-to-extract-more-water-from-florida-springs-causes-concern

(5) https://www.tampabay.com/news/environment/2021/03/11/companies-bottle-and-sell-floridas-spring-water-should-the-state-get-paid/

(6) https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/15/opinion/bottled-water-is-sucking-florida-dry.html

(7) https://www.bevindustry.com/articles/92452-bottled-water-bubbles-over-with-growth

(8) https://www.doughroller.net/personal-finance/the-bottled-water-industry-is-out-of-control/