Fifty Years of Storiesby Loye Barnard

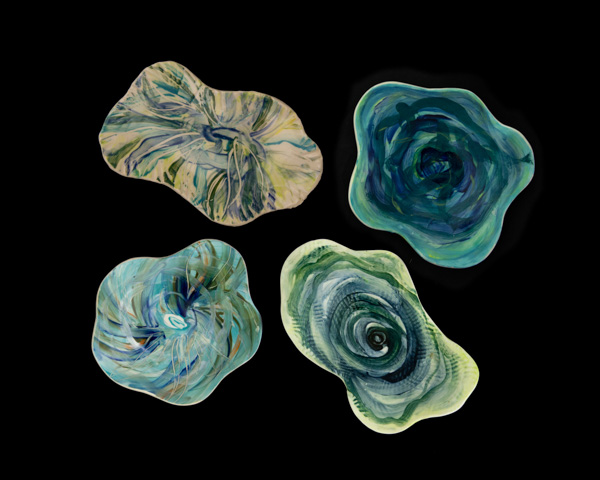

Working as the Ichetucknee Ambassador for Jim Stevenson, Loye Barnard built public support for the Ichetucknee by educating people about the health and significance of the springs and river. An artist as well as an advocate, Loye was inspired by her love for the Ichetucknee to create the plates featured here.

| I’VE LIVED NEAR THE Ichetucknee and collected stories over the past 50 years. Of course I was gone for 20 years. A hole had been cleaved, deeper than the aquifer we were trying to protect. It’s clear now. I could not have anticipated it. Government becomes the enemy of environment.

Back then I had a naive assumption that if we put the education and information where it should be, then we all could and would protect [and] do what’s best for the springs.

How could I have known differently that we were going through a process that did not lead to progress as beneficial?

Ichetucknee, 1960s, An Early Spring

The first stories we ever heard about Edgar Watson began here in 1964. For centuries the backwoods of north Florida was a virgin forest, a cathedral of longleaf pines. Spain owned this land and began offering Land Grants in 1790 to settlers who showed they could cope with its wildness. They burned and cleared and planted slash pine for turpentine. Beyond the pines the woods are crisscrossed with white sandy roads pale as moonlight. Each path through the dark understory of hardwood forests and broadening floodplain leads to a vibrant turquoise ribbon of river. Blue as midnight, deep-throated fountains of water rise and flow as the azure springs of the Ichetucknee.

As divers, my husband, Barney and I came to love the riverbed with its limestone crevices and continually shifting sands. We discovered an underwater archive revealing centuries of community life in north Florida. Centuries of man’s tools and animal remains ended their lives, their usefulness, on Florida’s river bottoms. We were awed with images of prehistoric creatures dying, driven to the water and killed by unknown hands. Knapped spear points, projectiles that did the deed lay among their ancient bones.

Years of layering in the river of lost or broken objects contributed to the detritus of ages. Rust-eaten muskets and hoe blades worn thin as paper from the 1800’s and white clay pipes we had only seen in Dutch Renaissance paintings.

But the chill that settled on us in our new home wasn’t from the water. It was the murdering antics of Edgar Watson. I was told at that time that I was a reincarnation of Mr. Watson’s second wife. Of course, we had no idea who this Watson character was or his wife, either. We had just been introduced to the person who made this proclamation, Russell Platt, an affable, eccentric transplanted from the northern climes of New England. Before long, we found ourselves caught up in the local lore of past and present. We were connected to centuries of men and women drawn to this bejeweled, clear sun-sparkling water and sustainable forests around Ft White.

Watson’s ill-famed story unfolds along the way, and Russell, with his curiosity and appreciation for story-telling opens a window to this world. Russ set a path through tales and legends that we were to follow for twenty years. Through his early stories we learned that Edgar was a man of mercurial moods. Some of them deadly. Later, we hear more authentic pieces of Edgar’s life though his relatives, our nearest neighbors, the Collins. Through them we came to know he lived within this river farming community with family members, many who would soon disown him. Russell’s lore also included Indians, Spanish explorers, hunters and agricultural settlers, and phosphate miners. A span of seekers over eons, found their way to the riverbanks of an enchanting, throbbing flow of a river rising out of the Floridan aquifer. Here they found survival, a living, sometimes wealth, from Ichetucknees’ pure water. Water this clear and cold for centuries restores one’s parched soul, body and mind, especially in the long dog days of Florida summers. The weight of impact of the many who still come to find solace in a less densely inhabited part of Florida continue to cloud the clarity and inadvertently poison the future of the Ichetucknee.

In the late 1950s Russell was already as white-crowned as the elderberry, blossoming along the upper Ichetucknee. Launching his old, battered canoe from the head spring, we could glide into high lacy bushes, shaking indigo purple berries from their loaded branches down onto a sheet on the floor of the canoe. The jam we cooked and jarred was delectable all year. But our attempt to produce a finished bottle of elderberry wine never evolved beyond tasting the sediment of crusty, musky juice.

Barney and I, with our two young daughters Kimber and Amelia, moved from Sarasota in 1964 having recognized our place of belonging in the backwoods of North Florida. We figured out how to make a living, for me painting, teaching, and for Barney–myriad jobs till he started logging the rivers for heart pine.

Logs frequently jammed as they swirled in the fast currents of the many circuitous bends of north Florida rivers. The rafts of longleaf pine trees cut for timber and masts for sailing vessels would be forced down, strewn like pick-up-sticks below the water where many still remain, locked for hundreds of years like sleeping princesses in fairy tales on the rock-bottom rivers of the Suwannee and its tributaries.

We met Russell because everyone we knew said we had much in common. He lived in Fort White, a couple of miles from the head spring. He had spawned an assemblage of small one room cracker houses that he slid together on logs, placing them, in the vernacular of southern house-building, on stacks of stones or rock. They were strung together with charming breezeways, brimming over with found objects—sections of mastodon bones, broken pieces of Spanish majolica, and relics of settlers’ derelict farming tools. Each room had an abundance of musty books—biography, archaeology, history, nature magazines—and collections of articles, many about the artifacts of the inhabitants and natural history of this part of Florida.

Russell had a tender affinity for the springs and the people who made up this quiet farm community. He frequently offered help to neighbors, anyone who might need a hand. He was a familiar figure with his shock of white hair and ‘caterpillar’ bushy black eyebrows, a meerschaum pipe, sometimes still smoldering with wisps of smoke in the jacket pocket of a frayed, seedy tweed, its fine cut evident of another life, further north. As he set to work, he’d remove his coat, and look for the nearest tree, a bare branch to support it, keeping it out of harm’s way. Then he’d roll up the sleeves of his yellowing dress shirt in preparation for the task.

He tackled anything folks might need, a chimney repaired, or a fence patched with wire he’d found at the dump, to contain a wayward milk cow. Sometimes he would engage in more serious projects than grass-cutting. He’d tackle digging a new drain for a septic tank or a burial hole for the remains of a beloved animal. He’d finish it with a stone or wood marker spiraled round with honeysuckle vine.

Lean and leathery, his strength was evident as he loaded a push mower in his venerable jeep. He enlisted anyone who might stop by his place, to spend the morning at the Ichetucknee cemetery, tidying up. Weeds were pulled, headstones, straightened. When Russ and I were busy a while, transplanting or corralling the likes of overbearing azaleas and the girls got weary of picking up twigs, they would choose a favorite gravestone. I’d have a sack with soft, strong paper and crayons ready to hand out. They played their morning away making rubbings off the weathered stones. Century-old tragedies enthralled their child-minds. Lovie Duncan and her daughter died together. A heart-shaped stone with a tiny, sculpted lamb encircled their names. One man’s headstone told us he was murdered very near this graveyard, by a neighbor. We still have those rubbings tucked away in a drawer of children’s art.

Sometimes we fixed a breakfast picnic to spread on an unmarked stone or marble slab. Russ would clean it heartily with a cord of Spanish moss. The dogwoods dappled the mid-day light, cerulean shadows limned sweetgum leaves on sun-warmed stone and the bobbing golden heads of the girls. He’d have a basket, a couple of mugs and a thermos of coffee with an abundance of milk, which he poured into two tiny porcelain teacups for my daughters—his grandmother’s from Connecticut, we were told. When Amelia was eleven, Russell gave her a delicate pair of pierced earrings, also from his grandmother, with ruby-colored garnets set as precisely as if a jeweler had plucked a hummingbird’s throat confining it to a cage of gold filigree. She still wears them, forty years later.

Both Kimber and Amelia were swimming fishes by the time they were three and four. Sliding off the hump of a slick black innertube to follow tiny musk turtles was always more fun than being tucked in the floor of a canoe. Russ pointed out where the Collins grist mill stood half way down the river on a spring run in the 1800’s. Still evident is an enormous cleft in the limestone off the bank where the wheel would have been for grinding corn. There was a post office and a general store for serving the sizable community.

Families, and neighbors would gather by the river when field and farm work slacked off through the week. Winnie Collins told me that once, late in the golden dusk, when you could barely discern the buckboards, with mule tails swishing, everyone indulged in her deliciously anticipated white mountain icing cake, studded with raisins, only to discover that the raisins were flies.

We spent delightful days throughout the year on the transparent Ichetucknee river in Russell’s canoe exploring spring flows and remnants of settlements along the runs. There is a Spanish mission site from the 1600’s, documented in St Augustine where 100 Indian boys and girls were baptized by priests near Fig Spring. The ancient fig tree is now only a fruity, tantalizing scent rising from a footstep in the spongy decaying loam along the water’s edge.

Peering through glass-bottom buckets Russell had meticulously soldered out of old tin pails, we’d slowly plunge them down. Each level to our delight, varied with riotous color. Brilliant liquid striations of azure blue and turquoise water, aquatic vegetation with streaming plumes of carnelian Foxtail, robust Red Ludwigia, intermingled with vibrant blue-green rippling eel grasses, darting tadpoles, tiny rainbowed minnows, water spiders, crayfish…a flowing current, an underwater silent circus. We searched into glowing, luminous bottom sands and white clay banks for pieces of china or fragments of bone. It was easy to envision the levels of history below our knees. Amelia was barely four years old when she lifted out a fingernail-sized piece of majolica, deeper blue than the morning sky. It almost completed the rim of a plate Russ had been piecing together for years.

We carefully cradled fragments of mastodon and mammoth teeth, pieces of rib or tusk of tiger. Camel femurs, inner ear-bones of whales. In our hands, we held remains of creatures that died in this water 12,000 years ago. One languid, drifting afternoon Russ identified from the canoe, a young mastodon skull with upper and lower jaws intact, a brain cavity the size of a basketball. Later taken to the Florida History Museum to document, some pieces were left there, some returned home with Russell.

Leeches, banded water snakes and fat-bodied amphiumas added creature enchantment to our forays. We gathered watercress, lush and green, for liverwurst sandwiches or for a delicate green version of vichyssoise, so delicious, with cream from our cow that we dared to compare it to the classic soup we savored many years later in travels through France. Our friend Russell had seeded this cultivated variety of cress before the park was purchased by the state in 1970. It is still evident today alongside the native version noted in the 1900’s, even though neither is ours to pick. Of course, we understand now the ‘introduced’ plant should not be there.

Drift down with the flow, down the Ichetucknee. Body suspended in time, mind set free. Swirl in glass clear currents, graze over slithering grasses of silvery-celadon green. Ease into blue-violet eddies surrounded by sentinels of orange-knobbed cypress knees. Wild persimmon boughs sway as branches of snow-white buttonbush catch on the fringe of your sun-warmed hair. A universe of fluidity, rainbow water…floating sky. A brilliant, transparent world of liquid cyan-blue, bubbling into existence from the depths of the earth. With its green-gold longleaf pines, regal lords of the sandhills, star-bursts of saw palmettos peering from hardwood hammocks under a cobalt sky, this treasure of a spring-fed river, is a repository of life. There was a time in the beginning of those halcyon days we knew we would live here forever.

Loye Barnard

“Thousands have lived without love, not one without water.” ~W.H. Auden

Ichetucknee, August 2020

Ft. White, Florida